At the 28th Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival (PÖFF) the spotlight shone on Georgian independent filmmakers under the theme “Independent Voices of Georgia.” This showcase offered a unique glimpse of a nation in transition, with Georgian filmmakers bravely exploring themes of independence, resilience, and innovation. Their films reflect the country’s evolving identity and unwavering commitment to powerful, unfiltered storytelling. From confronting historical wounds to navigating an uncertain future, Georgian cinema remains a force for voices that refuse to be silenced. The Georgian Film Institute (GFI), established in 2019 by leading filmmakers and industry professionals, emerged as a direct response to increasing government interference in the arts.

This year, Lana Gogoberidze, one of Georgia’s most celebrated directors, was honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award at the festival. At 96, she continues to inspire, presenting two iconic films to a new generation of viewers.

The featured films in the Georgian Spotlight section included a diverse range of works, each with its own unique perspective and storytelling style: Irine Jordania’s Air Blue Silk, Elene Mikaberidze’s Blueberry Dreams, Tato Kotetishvili’s Holy Electricity, Akaki Popkhadze’s In the Name of Blood, and Lana Gogoberidze’s Mother and Daughter, or the Night is Never Complete. Each of these films offers a unique and compelling narrative that is sure to captivate audiences.

I spoke candidly with three strong and independent female Georgian voices, Lana Gogoberidze, Irine Jordania, and Elene Mikaberidze.

Lana Gogoberidze

MP: Your films have a powerful narrative and a distinct visual language. They are often centered around assertive female protagonists who resist the status quo. How did this type of character emerge in your work?

LG: The roots of these characters run deep in my own life. At the age of seven I was separated from my parents and left to navigate a world without my loved ones. But even as a child I instinctively refused to be a passive victim of circumstance. I resisted, and that spirit became the foundation of my identity. Resistance wasn’t a choice – it naturally emerged within me. Two passions have always defined my life: poetry and cinema. From an early age, I was surrounded by intellectuals – directors, painters, writers – who gathered at my childhood home to recite poetry about resistance, power, and the strength of words. I remember my mother and her friends passionately discussing these themes. As I grew older I began writing poetry, even translating works I admired, like Edgar Allan Poe’s Annabel Lee. For me, poetry wasn’t just about beauty but a tool for defiance and self-expression.

MP: So when did you decide to pursue filmmaking?

LG: Filmmaking has always felt like part of my inheritance. My mother was a filmmaker, and growing up with that legacy left a strong mark on me. I always knew I wanted to follow in her footsteps. However, the social and political climate at the time made it difficult. I couldn’t go to Moscow to study filmmaking, so I enrolled at the University of Tbilisi instead. It wasn’t until Stalin’s death that I could finally travel to Moscow and pursue my dream of becoming a filmmaker.

MP: The Blue Room and your mother’s influence play significant roles in your work. Can you tell us more about them?

LG: The Blue Room was the heart of my childhood home. Before my mother was sent to the Gulag, it was the gathering place for her circle of friends – artists, poets, thinkers. Here, I first encountered the power of words as I watched grown men recite poetry with passion and conviction. That room shaped who I am. It symbolizes my mother’s spirit, her love for poetry, and her zest for life. When she returned from the Gulag after ten years, she was different – almost like a stranger. But over time she became the center of our lives again. Through her, I witnessed the incredible resilience of women. Despite everything she endured, she remained kind, generous, and unbroken. She embodied the strength of a woman who refused to let hardship dim her soul. The 20th century was shaped by men, but women like her must tell the story of our resilience and our view of the world.

MP: What does ‘resistance’ mean to you in personal and cinematic terms?

LG: My mother was a true example of resistance. Even in the face of immense suffering, she never let her circumstances define her or her relationships with others. She always remained kind, never letting negativity taint her spirit. For her, literature became a tool of protest – a way to voice the desire for freedom and independence. She believed that resistance comes in many forms, from protecting your inner peace to using art as a sharp, emotional force to challenge oppression.

MP: Georgia’s political landscape is evolving, with increasing tensions surrounding pro-Russian policies and threats to freedom of speech. How do you feel about the current situation?

LG: It’s a deeply troubling time for Georgia, but we will not return to the dark days of Soviet-era censorship. We are stronger now, and our desire for a free, independent Georgia remains unwavering. We want to be part of the European Union, and I am confident we can achieve this. People can now take to the streets and express their view – something unthinkable during Soviet rule – which gives me hope. Our collective will is our greatest strength.

MP: What message would you give to young filmmakers and artists who fear censorship or restrictions in today’s climate?

LG: We must stand together. While we may not face the same kind of censorship we did during the Soviet era, the potential for restrictions still exists. We must remain united. We need to take action, whether it’s through protest, writing, or creating art. I still do this today. Our greatest gift is solidarity. We need each other now more than ever – within Georgia and with our friends in different nations. We can ensure our voices are heard, and our freedom remains intact.

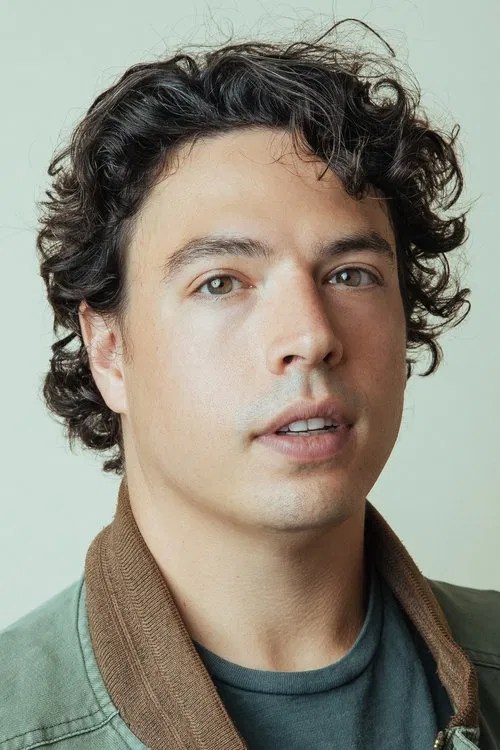

Irine Jordania

MP: How does it feel to have your debut feature screened for an international audience?

IJ: I’m overjoyed. It’s an incredibly special moment, both for me and my team. We’ve spent over two and a half years making this film, and the process wasn’t easy, especially with the challenges posed by the National Film Center’s restrictions and censorship. Finally seeing the film on-screen and witnessing the audience’s response is truly rewarding. At a time like this, international platforms are crucial for us. We need spaces to share our voices, which are often stifled back home.

MP: Can you elaborate on what you mean by censorship from the National Film Center?

IJ: The National Film Center is the key institution for filmmakers in Georgia, especially for independent voices. It’s the primary source of funding and authorization. But in recent years this has changed dramatically. There’s been a clear shift toward restrictions and censorship for filmmakers, artists, academics, museums, and even journalists. Since October of this year, with the implementation of pro-Russian policies, the government has rolled out tools that curtail freedom of thought and expression. It’s a difficult time for anyone who values creative and intellectual freedom.

MP: What was your inspiration for this film?

IJ: The film began with a simple voice message from a relative. You’ll hear some of those voice messages woven into the narrative. The filmmaking process itself was quite unconventional. We didn’t start with a traditional script; instead, the story unfolded organically as my team and I interacted. Our actors brought personal experiences into their roles, so it felt like a collaborative, evolving process from the beginning.

MP: How did your cinematographer contribute to the film’s unique aesthetic?

IJ: We wanted to portray the city as minimalistic – almost like a fleeting glance. The cinematography was driven by the characters’ perspective of the city. We chose random, seemingly inconsequential shots to create a sense of detachment, like passing glimpses of everyday life. The visual language of the film is loose and open-ended, with the narrative taking a back seat. This approach allows the audience to fill in the gaps and interpret the deeper meaning without relying on too many dialogues or overt storytelling. It’s about creating space for the viewer to engage more personally.

MP: How do you raise funds for your films in a climate where independent voices are suppressed?

IJ: It’s not easy. Funding is scarce, but we’ve secured some support from the Georgian National Film Fund. We also seek financial assistance through competitions and partnerships with organizations like the Georgian Broadcaster. Additionally, some producers, such as Elene Margvelashvili, genuinely champion independent voices and have been crucial in helping us bring our vision to life.

MP: As a final question, do you have a message for other independent filmmakers?

IJ: Absolutely. My message is simple: I stand with my people, and we will continue to fight for justice and freedom. We must support each other, especially in times like these when our voices are being suppressed. Together, we can push back against censorship and continue to create meaningful, impactful work.

Elene Mikaberidze

MP: What inspired you to pursue filmmaking?

EM: From an early age, I was completely enchanted by the magic of cinema. I would collect movie tickets and magazine cut-outs – small treasures that sparked my obsession with films. However, life took me down a different path for a while. I focused on studying film and nationalism, particularly exploring Georgian cinema, war, and identity. But my true filmmaking journey began after a trip to visit my grandmother. The journey was eye-opening; I had to pass through three military checkpoints and witness the harsh realities of life on the border, especially in the occupied regions. I interviewed families and absorbed everything I could. When I returned to Belgium I planned to write an academic paper, but I found myself writing a script instead. That was when I knew I had to follow my passion for filmmaking.

MP: How did you transition to practice in filmmaking?

EM: It wasn’t an easy transition, but it felt inevitable. First, I had to learn Georgian since I didn’t speak the language at all – I was raised speaking French. Once I became fluent I returned to Georgia and began working on film sets. Luckily I found a producer at Nushi Films who believed in me. I started as a production assistant from the bottom, learning everything on the job. Slowly, I worked my way up, moving into set and costume design and gaining invaluable experience on larger productions. I honed my craft with each project until I was ready to make my own films. My first short film, Cadillac, was a major step forward, followed by Blueberry Dreams.

MP: Can you tell us about the production of Blueberry Dreams, your latest documentary?

EM: Blueberry Dreams was a long journey. Initially, I wanted to film it in 2019 with my young cousins who live near the border. However, due to political unrest and the pandemic, everything stopped. The checkpoints were closed, and I felt completely stuck. That’s when I reached out to my producer, and soon after I met Elene Margvelashvili from Parachute Films. Together, we worked tirelessly to refine the script. In 2020, we submitted it to the Georgian National Film Center and were thrilled to win the competition. However, the pandemic delayed everything, and the waiting felt agonizing. Eventually, I travelled as far as I could to the border, where I met countless families and children, interviewing them about their lives. That experience reignited something inside me. Amid the chaos, my DOP and I found ourselves on a blueberry farm where we met two families, much like my cousins, struggling with their own stories. It was there, on that farm, that the film truly began to take shape. The political backdrop of their lives and their struggles sparked my curiosity and became the core of the documentary. The production faced numerous challenges, especially funding. Aside from the Georgian National Film Center’s competition win, the film was co-produced in Belgium and France. The process took five years, but it was a journey I wouldn’t trade for anything.

MP: What other challenges did you face during production?

EM: As I mentioned, the initial funding came from the Georgian National Film Center, but all independent filmmakers must go through them. While it’s a vital resource, the funding comes with many restrictions. For example, any delay in the production schedule or deviation from the original script can lead to fines. I was fined for using an extra tripod and painting something white that wasn’t planned initially! The bureaucratic hurdles were frustrating, but we navigated them as best we could. It’s all part of the struggle of making a film in such a restricted environment.

MP: What does the future look like for Georgian independent filmmakers?

EM: One thing that gives me hope is that we are not alone. There are 450 filmmakers in Georgia; together, we are a community. We support each other, share experiences, and fight for our right to tell our stories. I’m optimistic that we will be able to push for changes in European legislation, allowing us to enter co-productions without needing state funding. It’s a tough road ahead, but I’m confident that, despite the challenges, we are in a good situation. We are still fortunate to be alive, express ourselves publicly, and create art—even in the face of adversity.

First published in the International Cinephile Society in 2024